Bottom Line:

The world is not in the midst of a sixth mass-extinction, but we are witnessing declines in the size of wildlife populations. To help wild populations recover, we should:

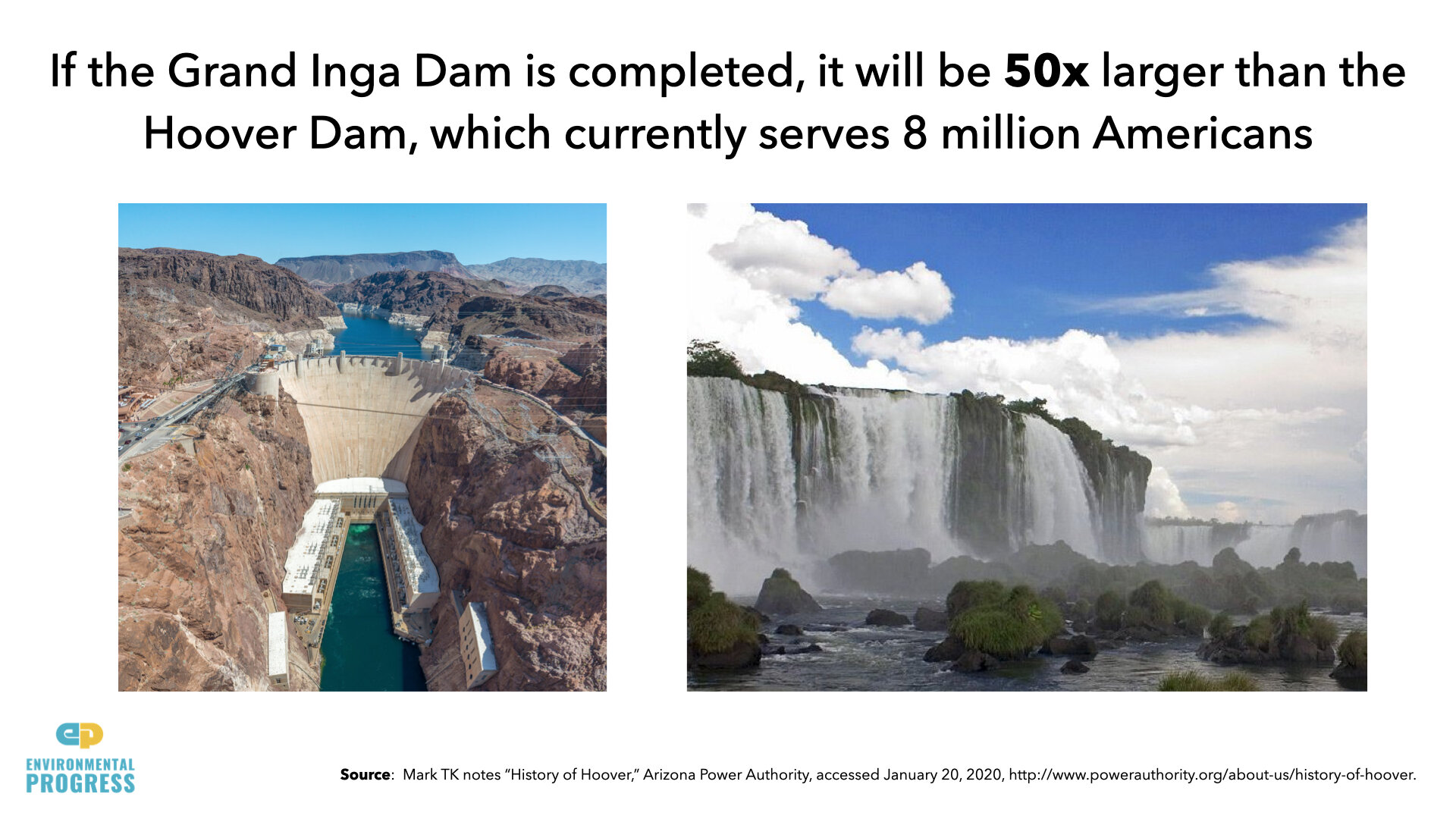

Transition away from wood fuel and charcoal, which disproportionately destroys habitat area, to more land-efficient energy sources like hydro and LPG

Promote economic growth in developing countries so they may have the ability to use less nature and put more resources to conservation as many wealthy nations have been able to do

FAQ

What is a ‘mass extinction’?

A mass extinction is a period of geologic time marked by a dramatic decrease in biodiversity. Scientists have used the fossil record to mark out five such periods in earth’s history, which are hypothesized to be initiated by major crises to the ecosystem, such as meteor impacts, volcanic eruptions, and/or great changes to the climate.

A study of the marine fossil record indicates that Earth probably lost about 25 percent of its species in past mass extinction events.

How many species are going extinct today?

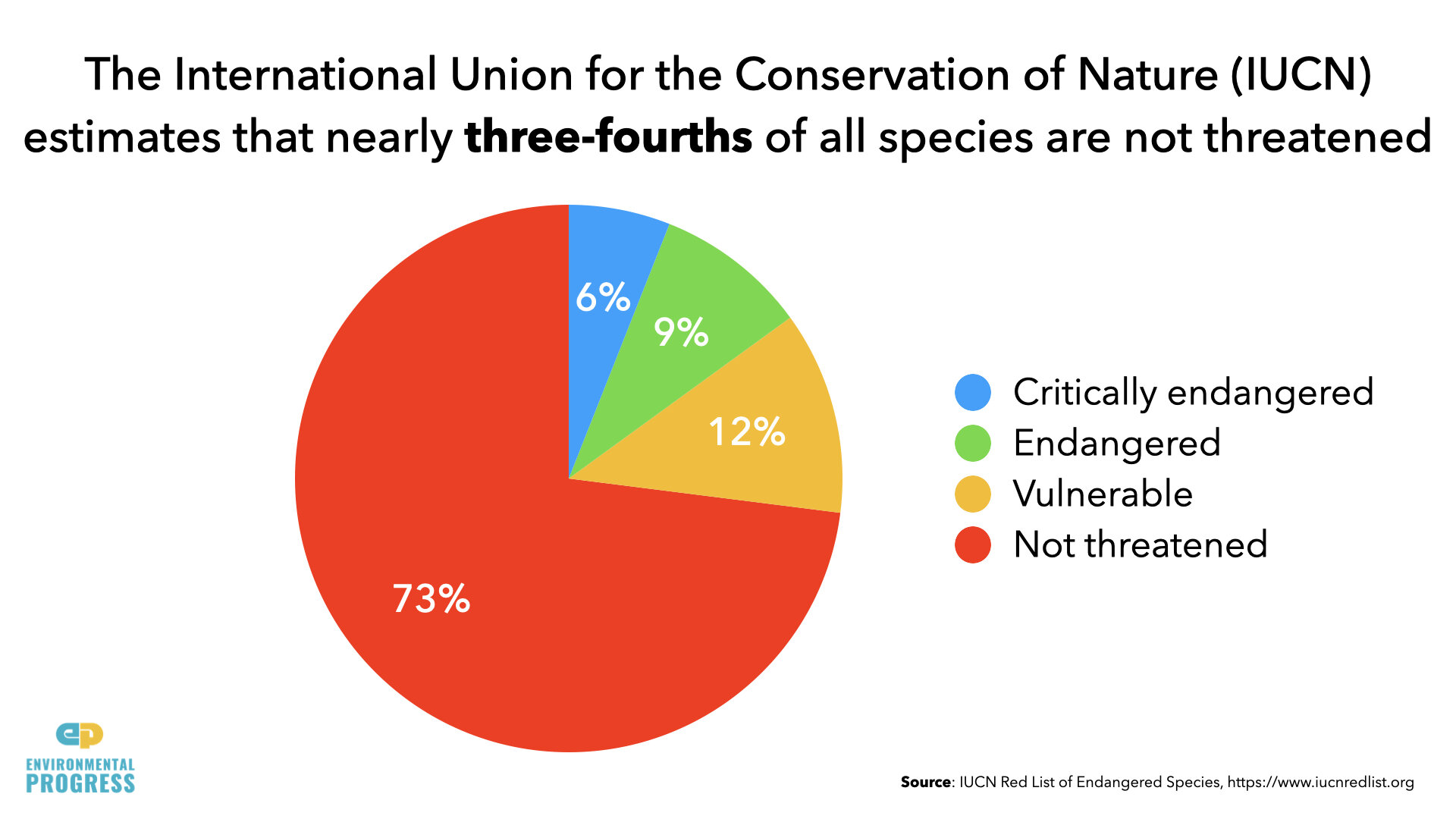

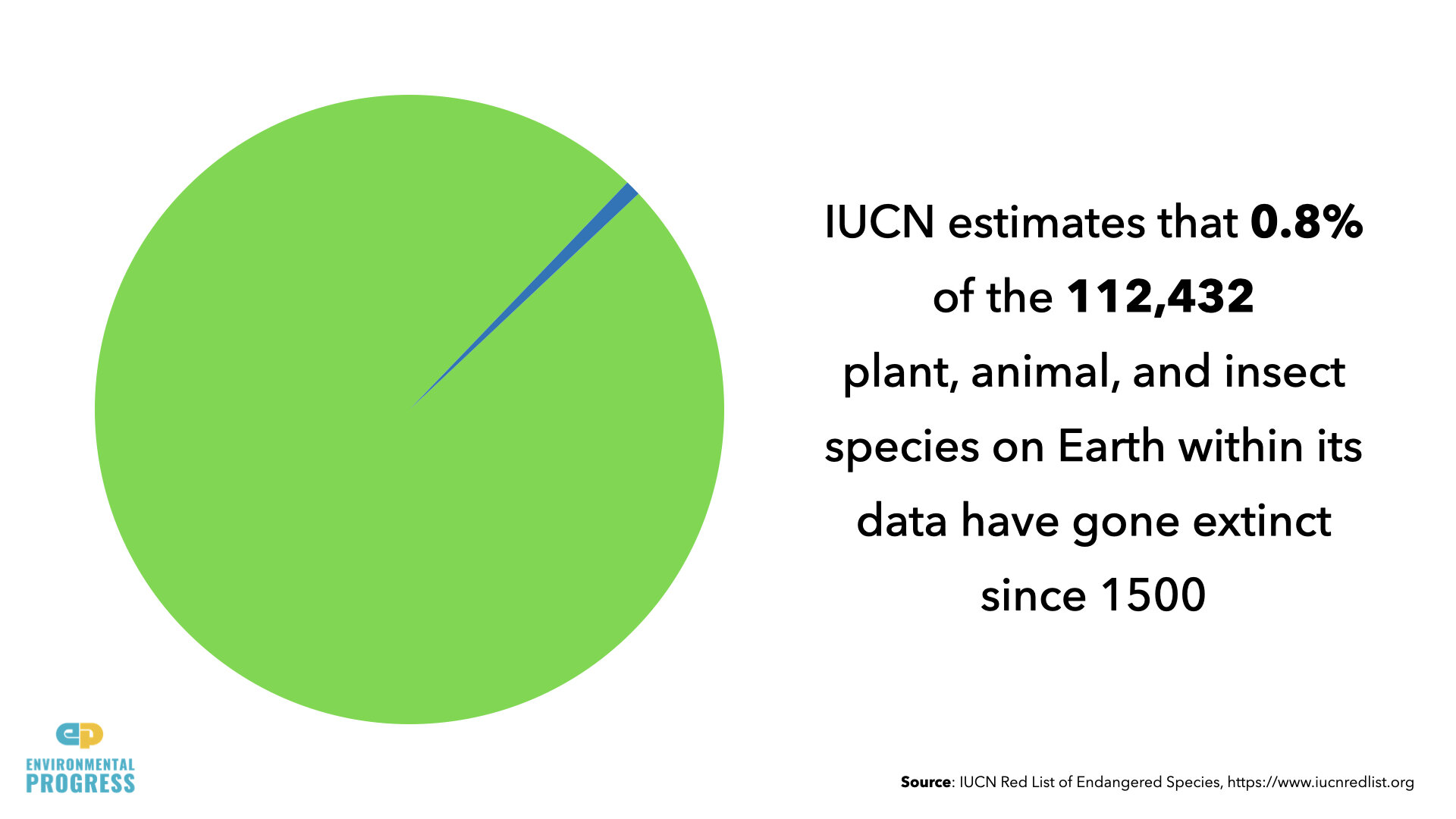

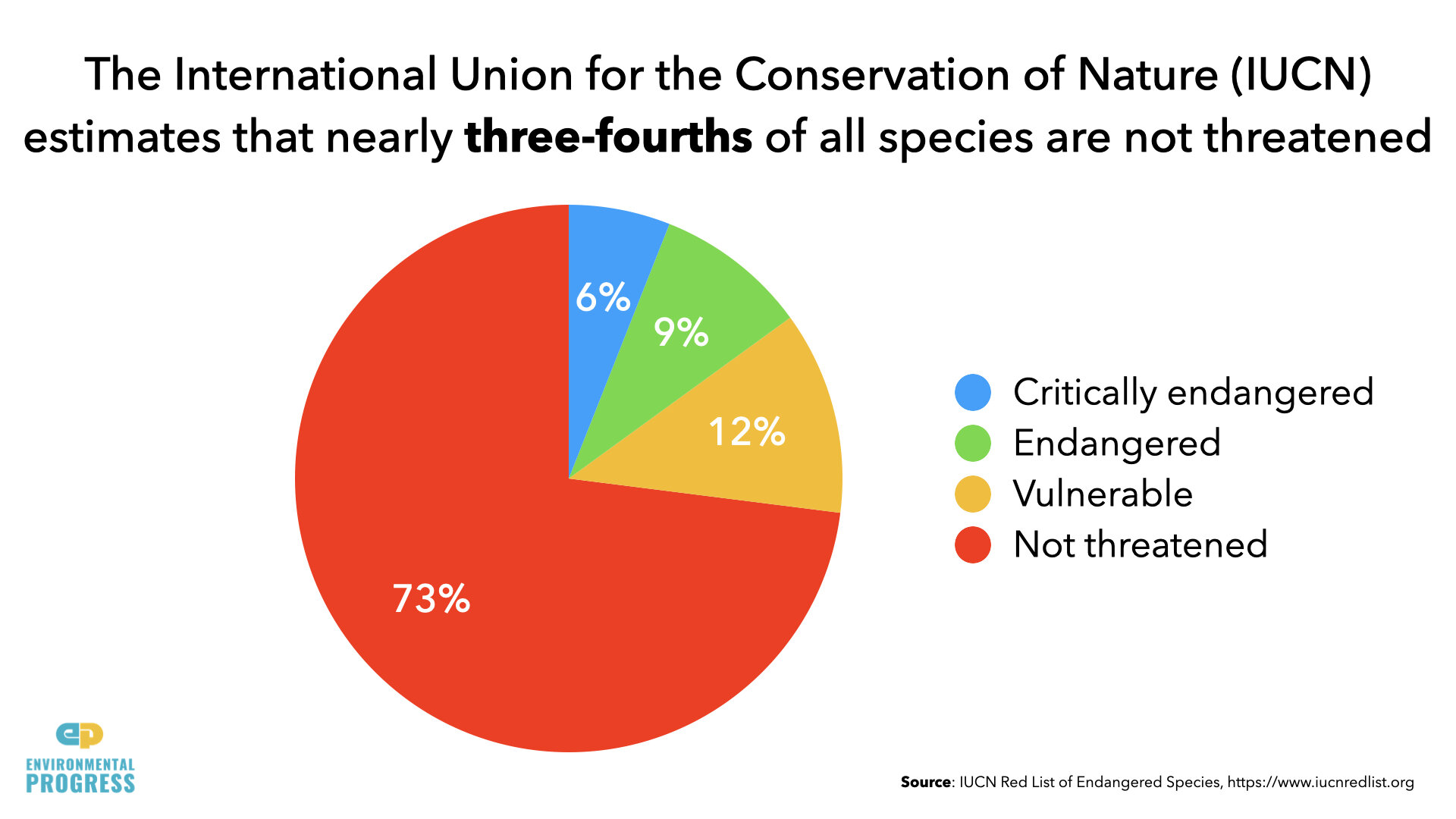

The IUCN has estimated that 0.8 percent of the 112,432 plant, animal, and insect species within its data have gone extinct since 1500. That’s a rate of fewer than two species lost every year, for an annual extinction rate of 0.001 percent.

In fact, the significant increase in biodiversity during the last 100 million years massively outweighs the species lost in past mass extinctions.

How come scientists and environmental activists claim we are presently in the midst of a human-caused mass extinction?

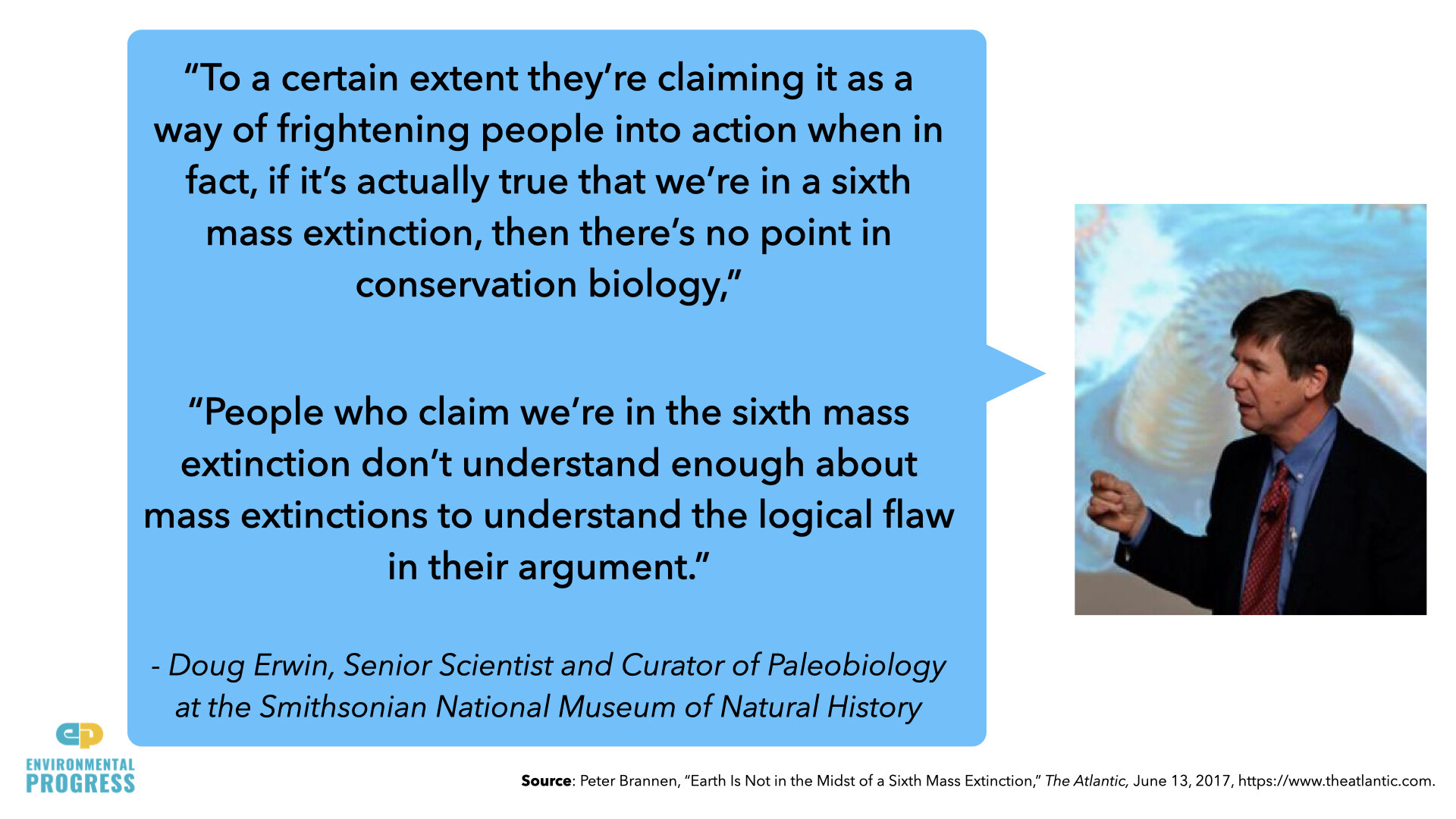

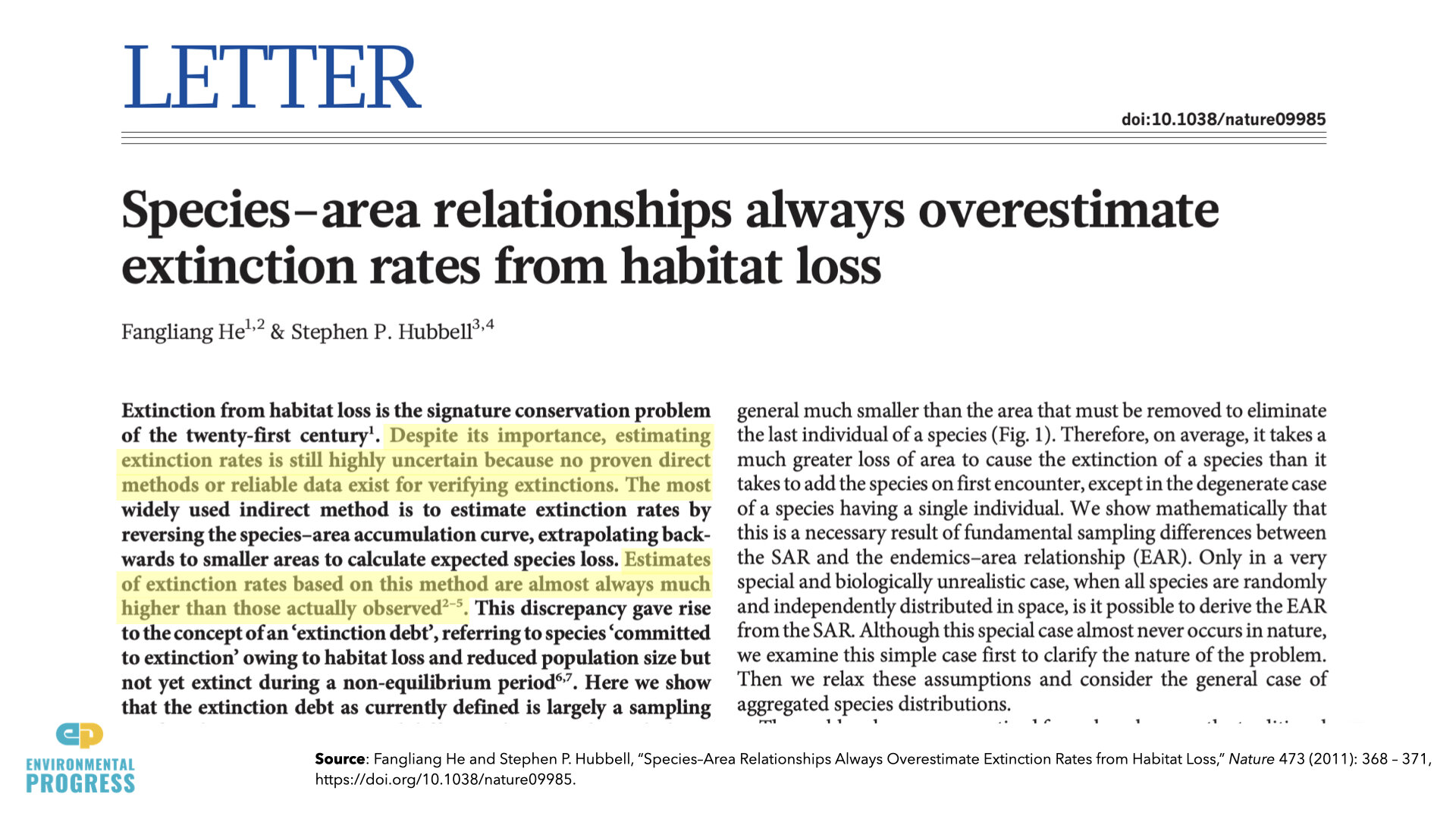

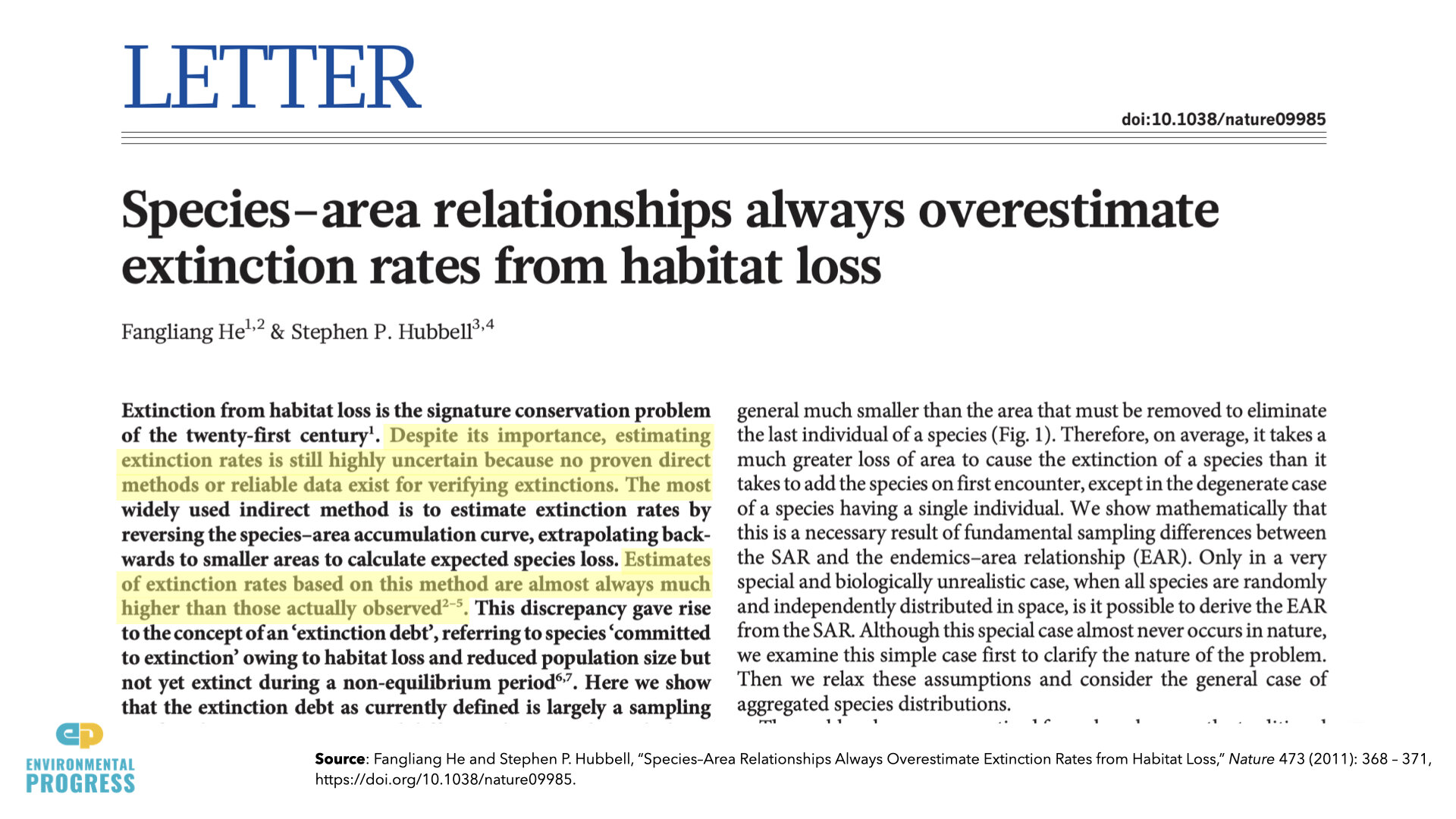

Claims that the extinction rate is accelerating and that hundreds of thousands of species are doomed to go extinct are based on very complicated models that rely on many assumptions that aren’t supported by observation.

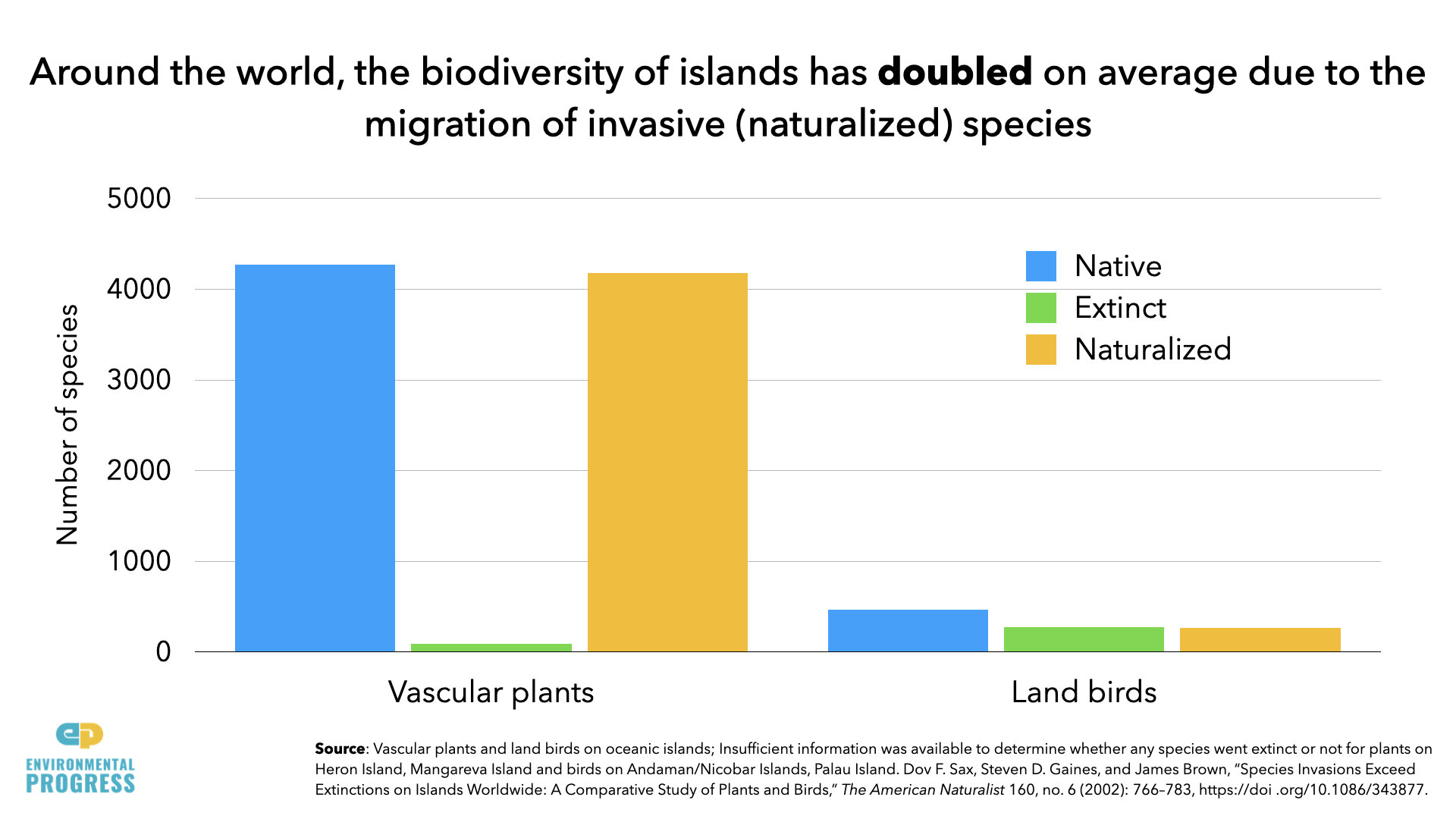

Fortunately, the assumptions that many of these models rest upon proved to be wrong, and it is becoming clear that these models have significantly over-predicted species losses. In fact, the biodiversity of islands around the world has actually doubled on average. In Europe, the number of new plant species has surpassed the number of documented plant extinctions over the past 300 years.

Environmental activists and scientists may have good intentions about raising the alarm about wildlife loss in hopes of inspiring conservation action, but the evidence doesn’t support that humans are causing a mass extinction.

Further, their advocacy may actually be undermining conservation efforts. If people think it is too late to act and there is no stopping an accelerating crisis, they will likely feel that action to protect wildlife is irrelevant.

If we’re not in a mass extinction, what’s the problem?

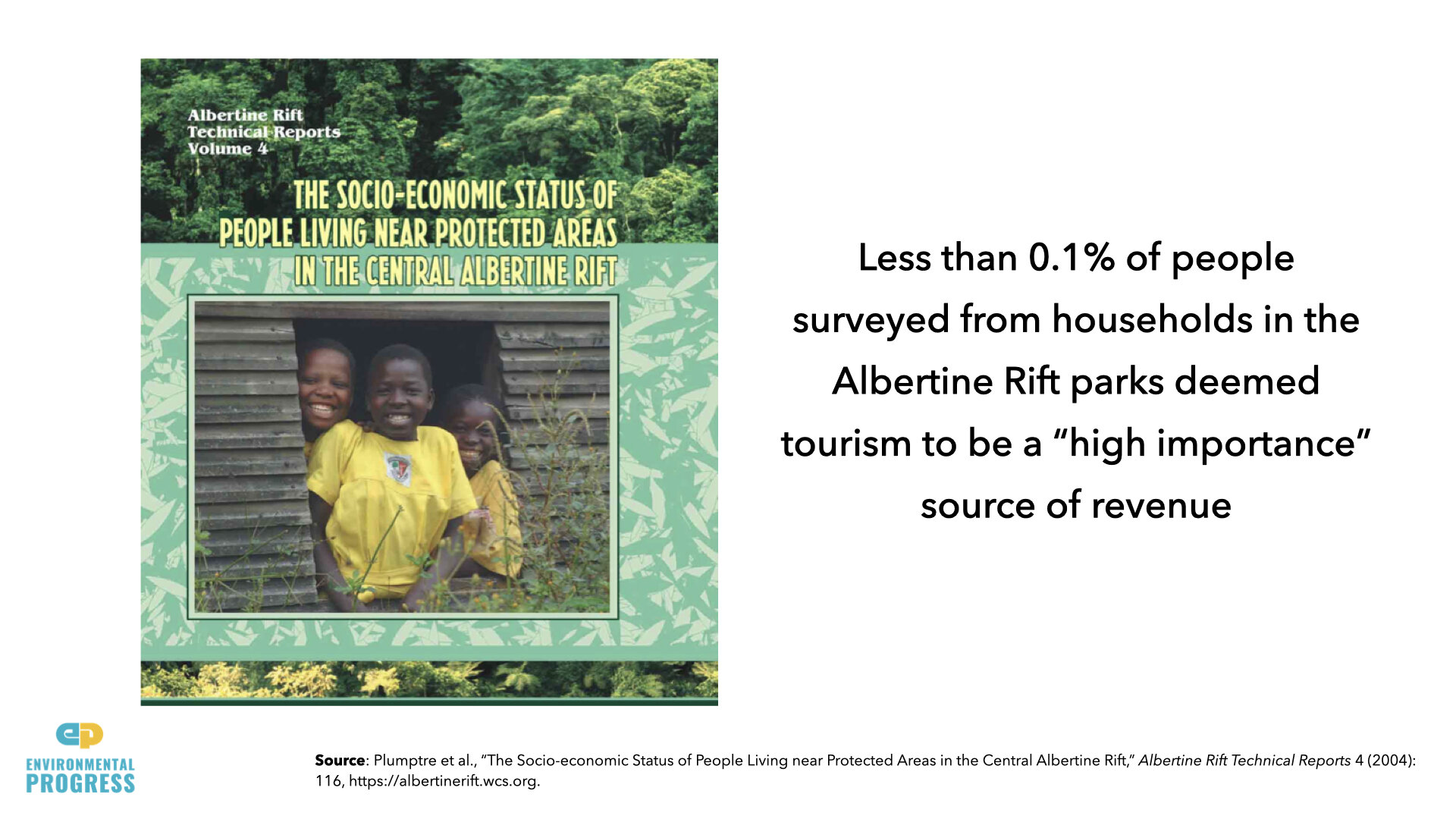

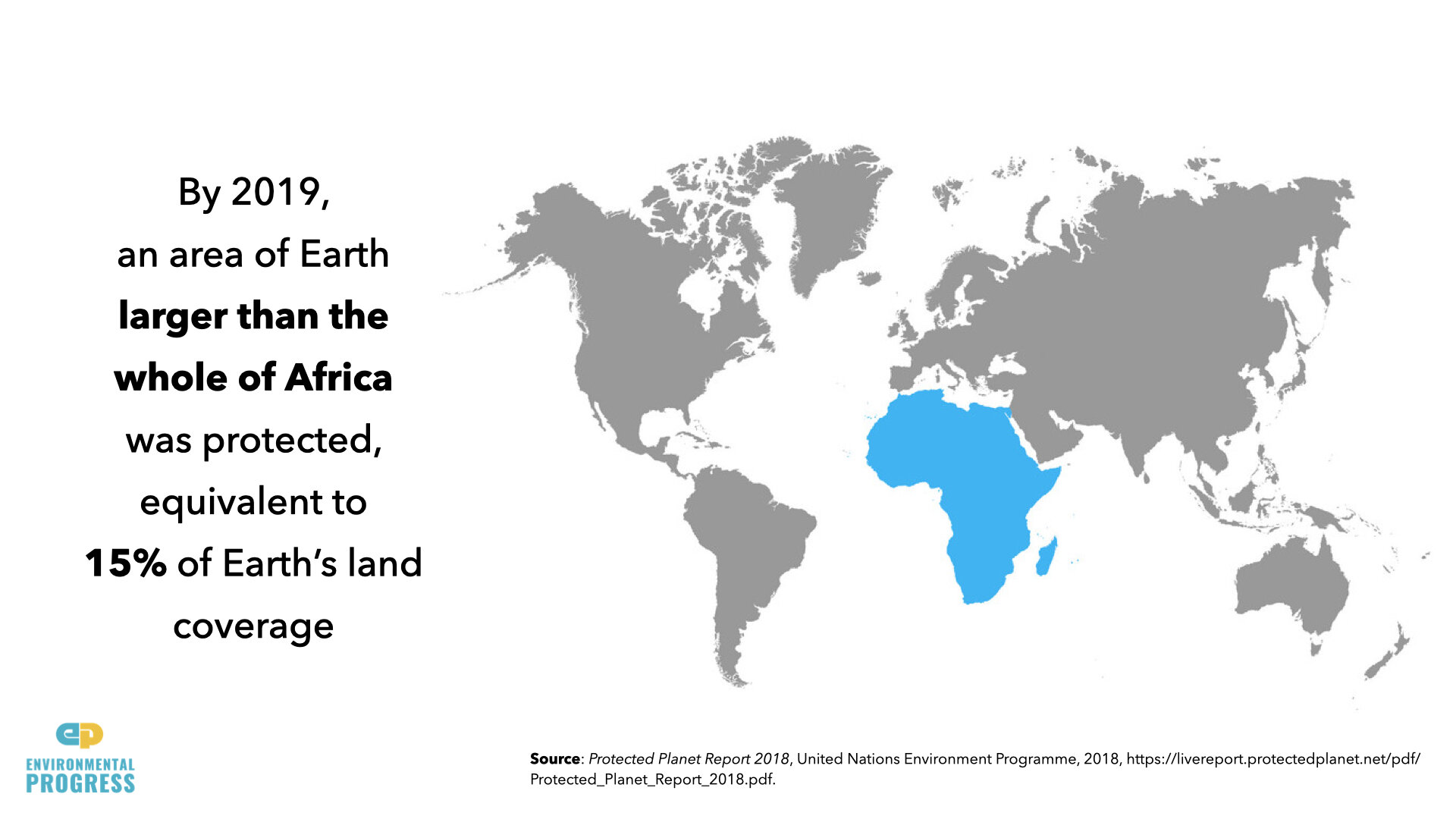

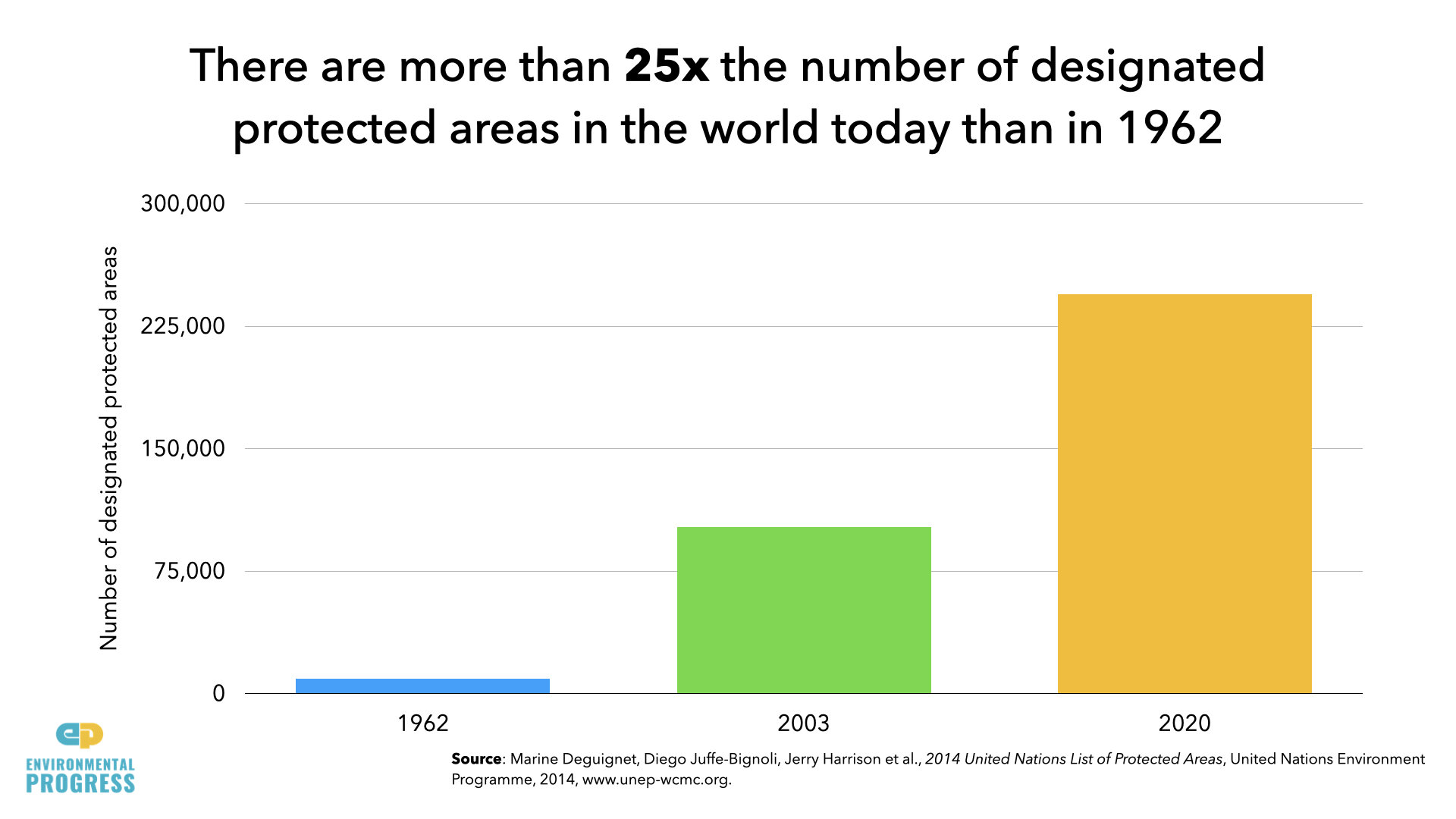

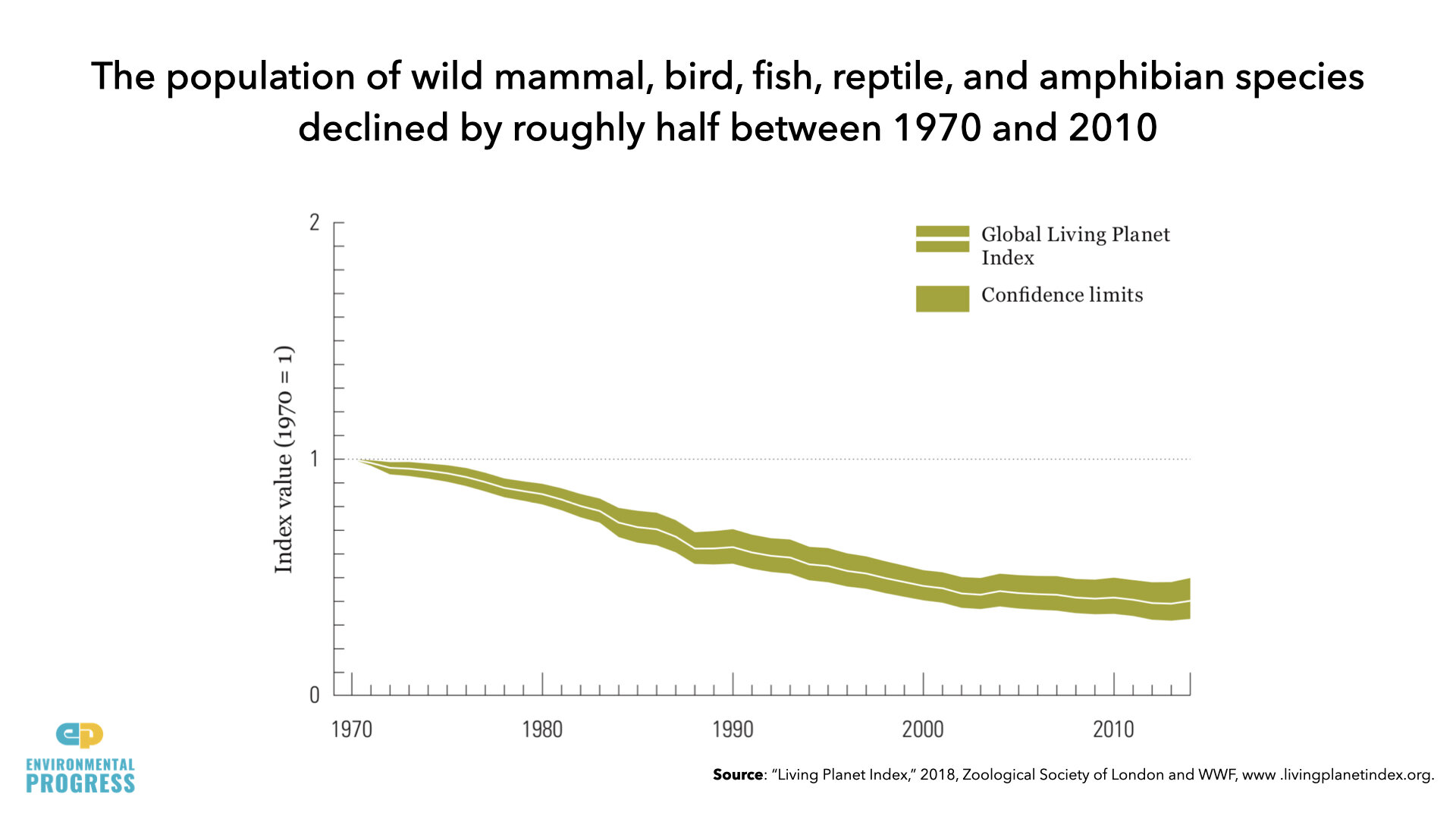

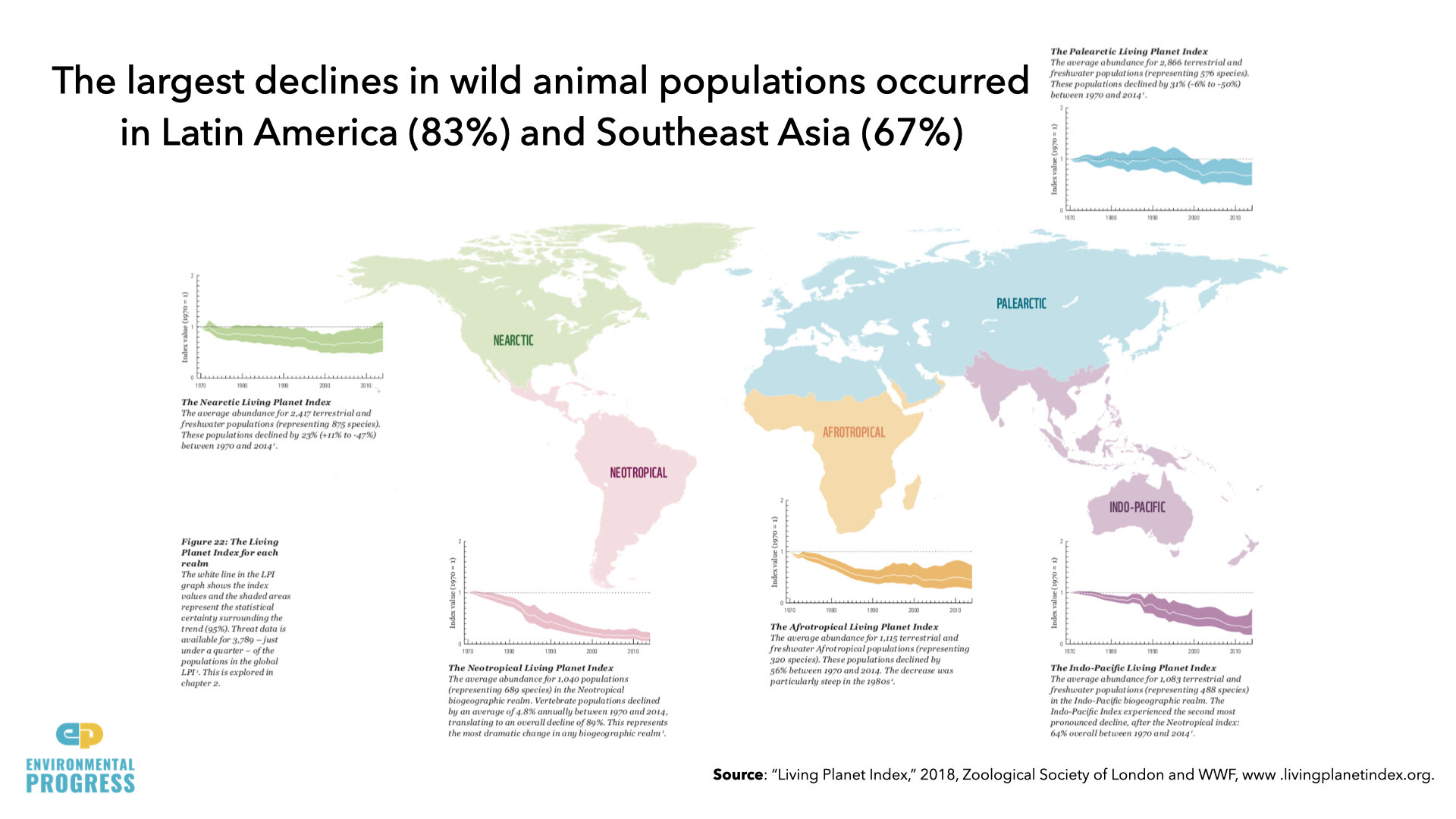

The real problem is not extinction but rather the decline in size of animal populations and their overall habitat. The populations of wild mammal, bird, fish, reptile, and amphibian species declined by roughly half between 1970 and 2010. These impacts are worst in developing countries, and have occurred in spite of a doubling of land areas protected since 2003.

What’s the primary threat to wild animals?

Many environmentalists and conservationists claim that fossil fuels and economic development are responsible for the decline in population numbers. However, this couldn’t be further from the truth.

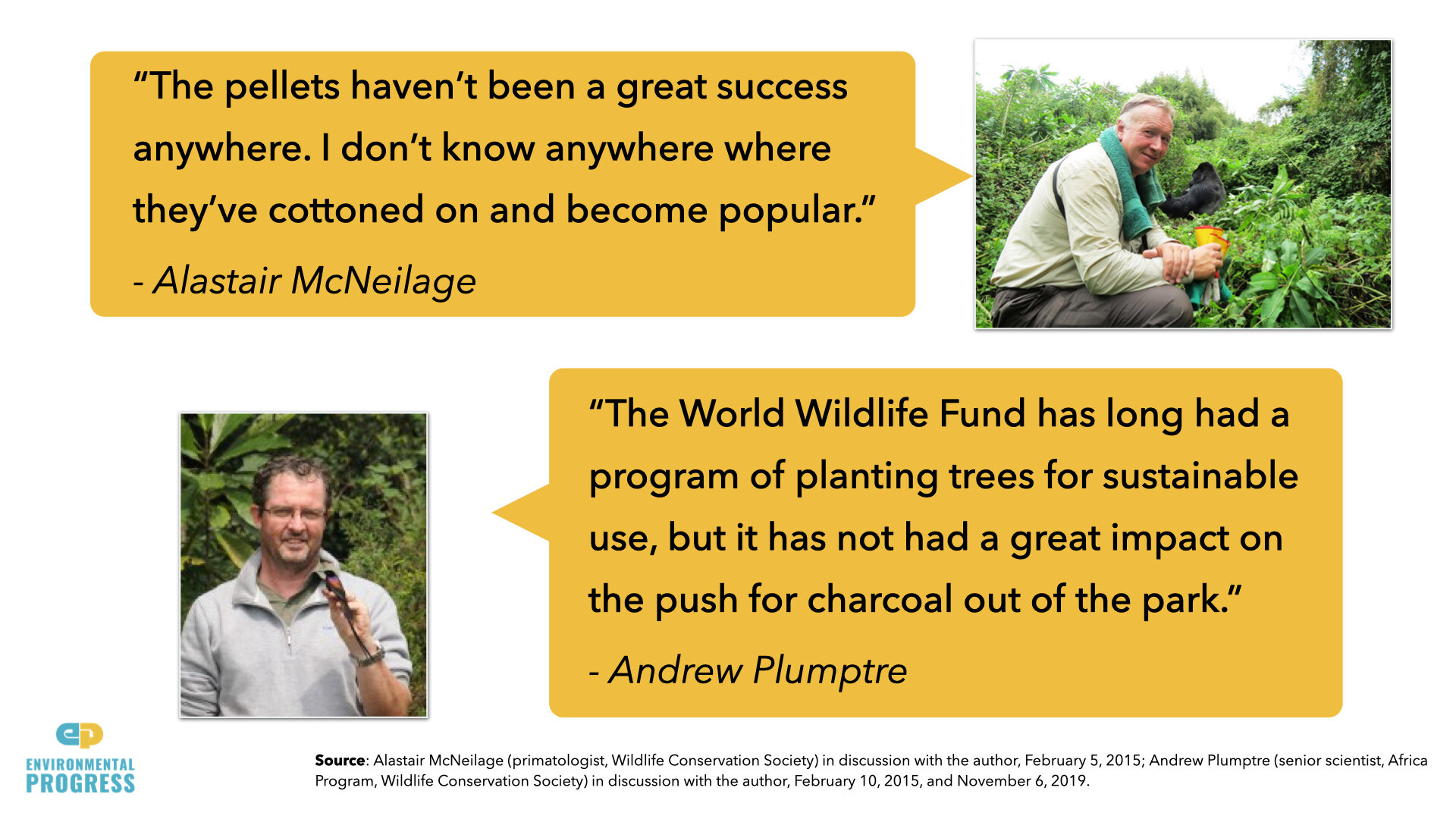

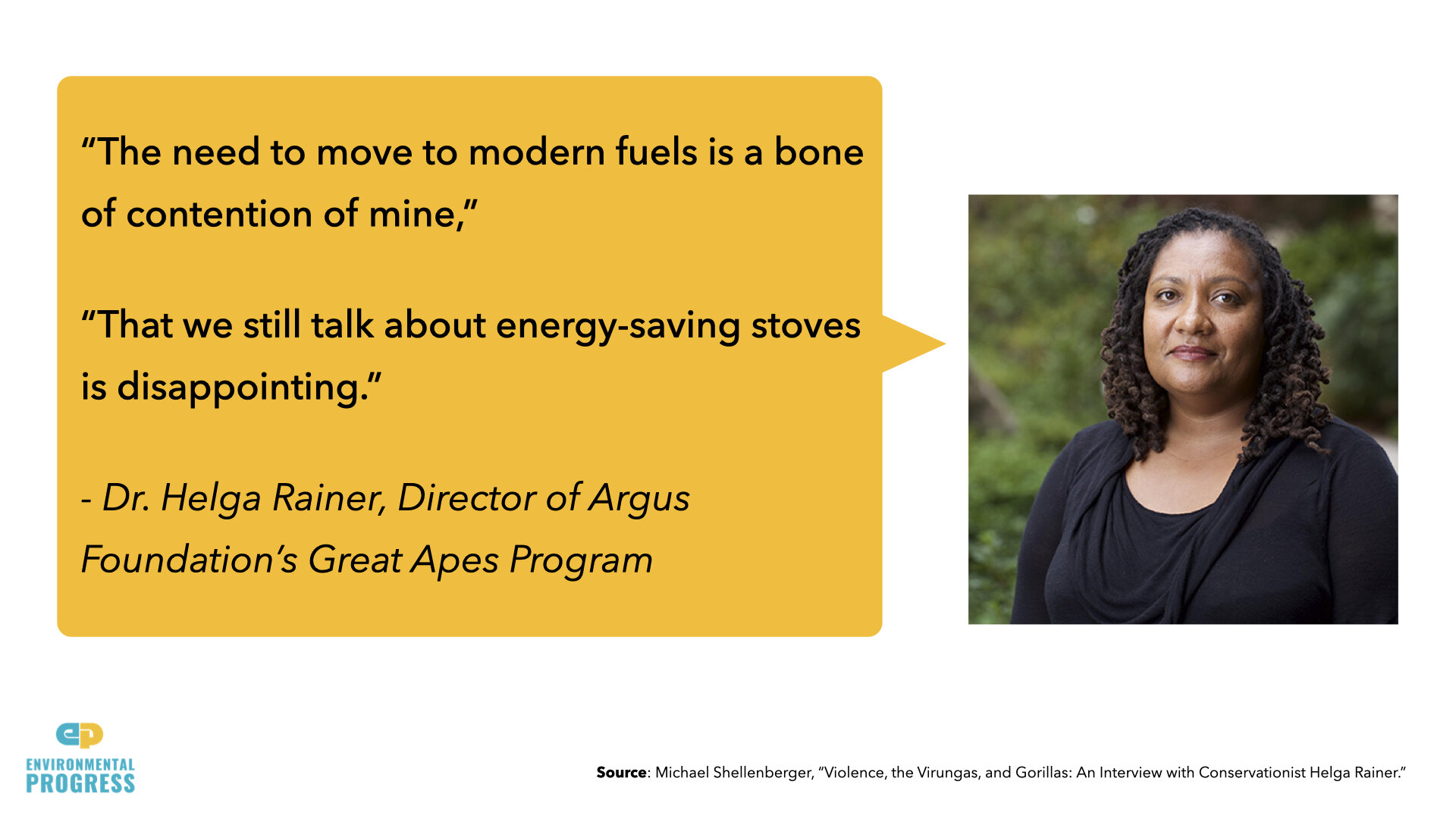

In fact, denying developing countries access to fossil fuels and economic growth is among the largest threats to wild animals. Making charcoal and burning biomass are top drivers of tropical deforestation, and is still the primary source of energy in Sub-Saharan Africa.

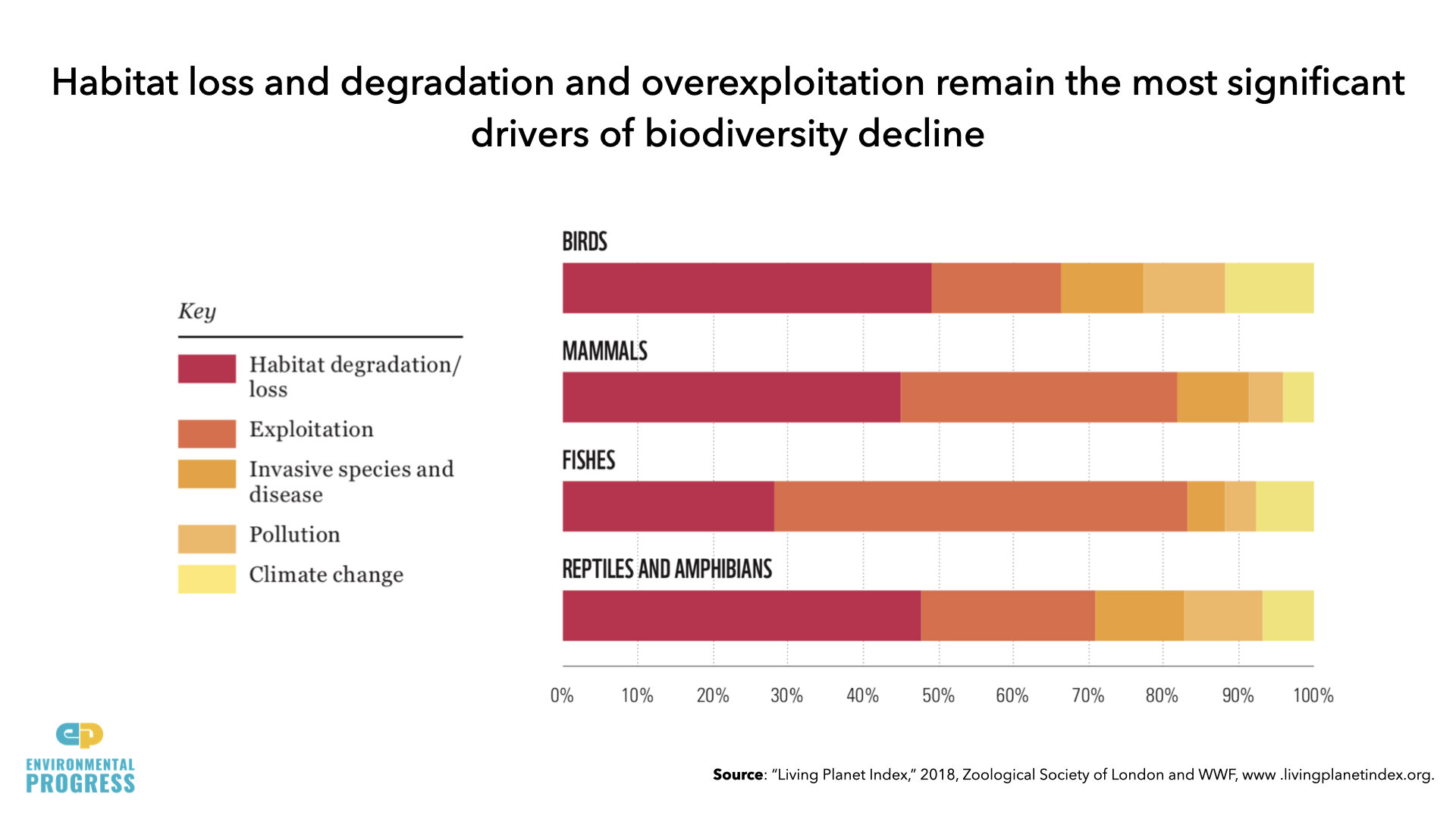

Others claim that climate change is the most serious threat to wildlife today. In actuality, loss of habitat and exploitation of resources significantly outweigh climate change as drivers of biodiversity declines.

What’s the solution to wildlife loss?

The most important factor in helping wildlife populations to recover is to cut our reliance on biomass. Ultimately, for people to stop using wood and charcoal as fuel, they will need access to liquefied petroleum gas, LPG, which is made from oil, and cheap electricity. Researchers in India proved that subsidizing rural villagers in the Himalayas with LPG reduced deforestation and allowed the forest ecosystem to recover.

As nations become wealthier, they are able to use less nature and therefore set aside more habitat as protected area. If developing countries have security, peace, and industrialization of the kind that has lifted so many nations out of poverty in the past, we will continue to see a trend of increasing conservation and environmental protection.

Extinction Slides